You are what you read

The year's hottest accessory is neither a bag nor a jewel. Clare St George on the unctuous, delectable and relentless cult of Butter

I bought a copy of Asako Yuzuki’s Butter on the way home from work. It was on the heftier side – 464 pages – and even as a paperback, slightly more authoritative in dimensions than the other books, its vivid yellow packaging beaming through the Waterstones stacks. I did not pay extra for a carrier bag, so I clutched it on the high street like a Fendi Baguette. Passing Tesco, I remembered that I needed butter to cook with that evening. So I walked down the dairy aisle, Butter in one hand, butter in the other.

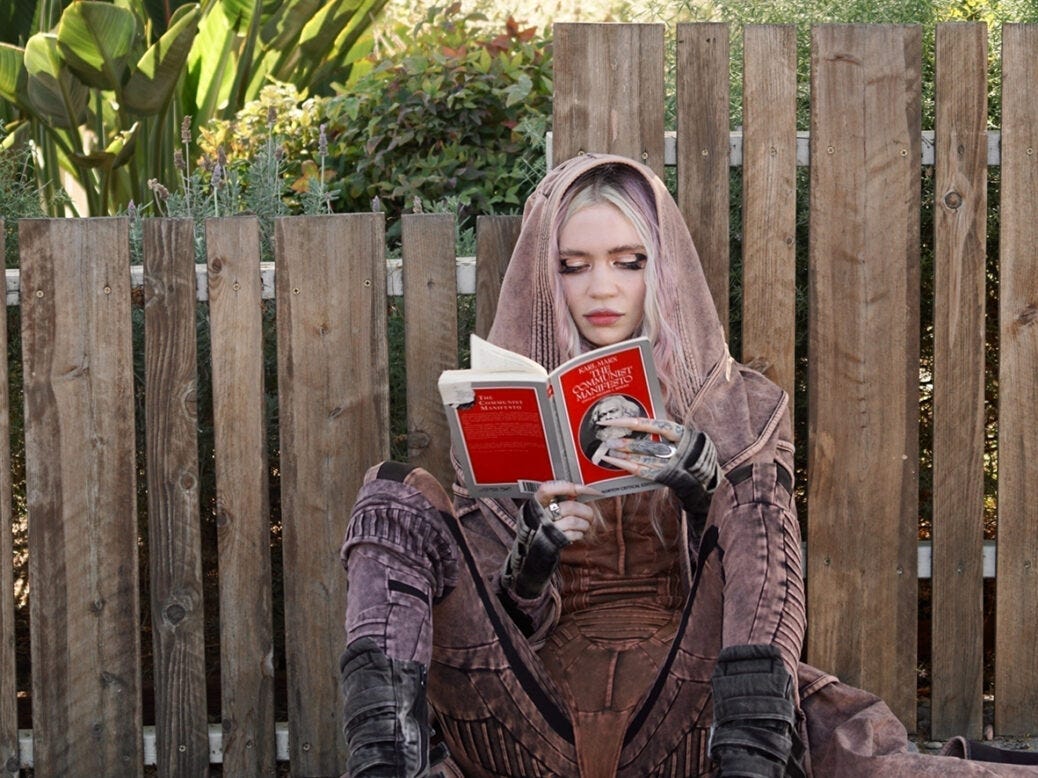

I am not the first, nor the last, woman to carry Butter in public. There have been many documented sightings on the London Underground – the city’s main digestive system, and busiest fashion runway. Reading, like wired earphones, became cool again after Covid. And like all trends, it quickly became a precarious affair – verging on irony. Grimes loitering with the Communist Manifesto after her divorce with Elon Musk; Kendall Jenner photographing The Year of Magical Thinking on her sun lounger while on a getaway with the Biebers; celebrities often use reading as a PR tool, an indication that they can think critically. As do regular men… by which I mean, white men reading Bell Hooks’ All About Love upside down.

The union between reading and performing falls flaccid in certain hands. You sir, yes you on the Suffragette Line, what are you trying to do here?

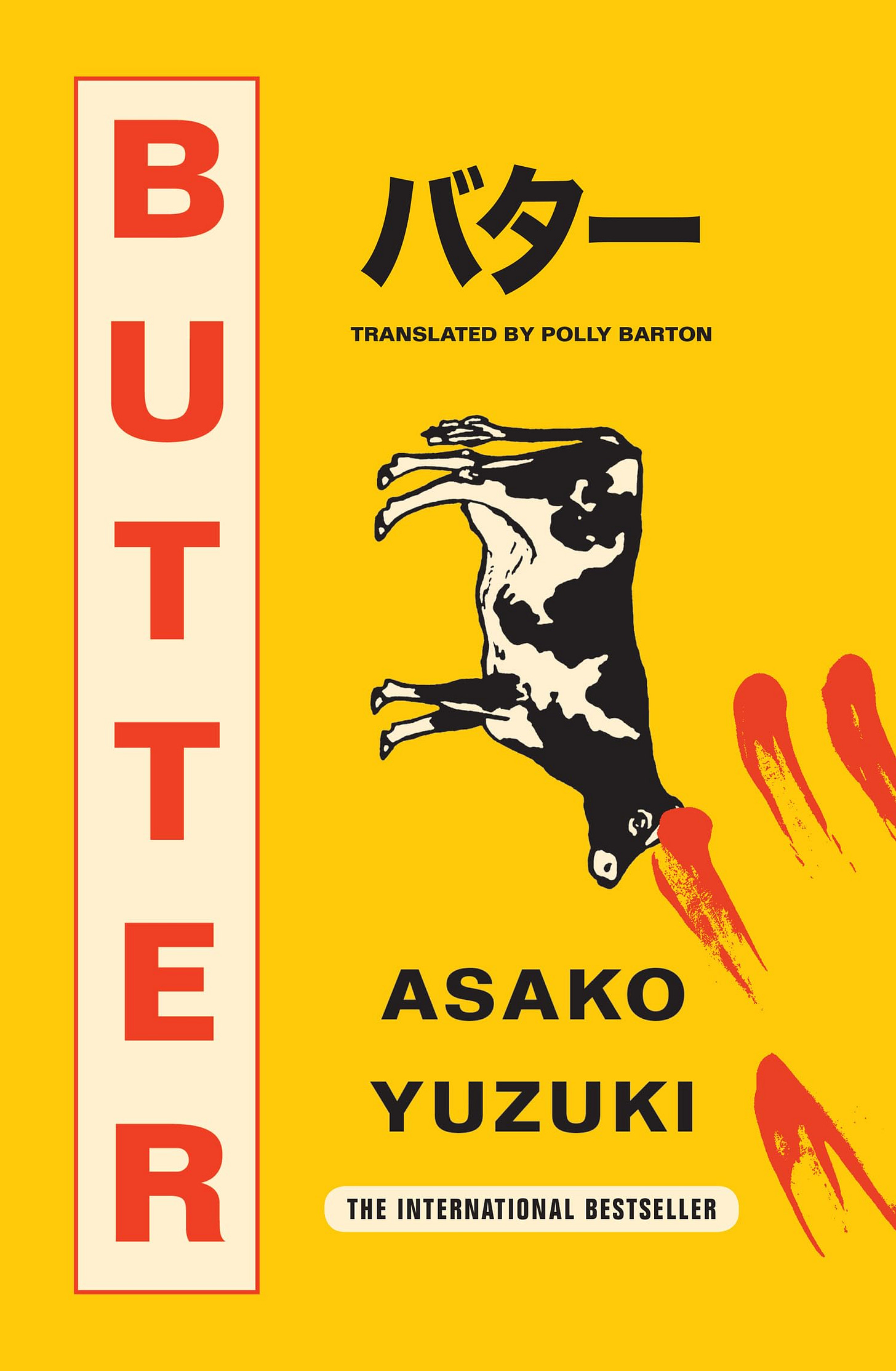

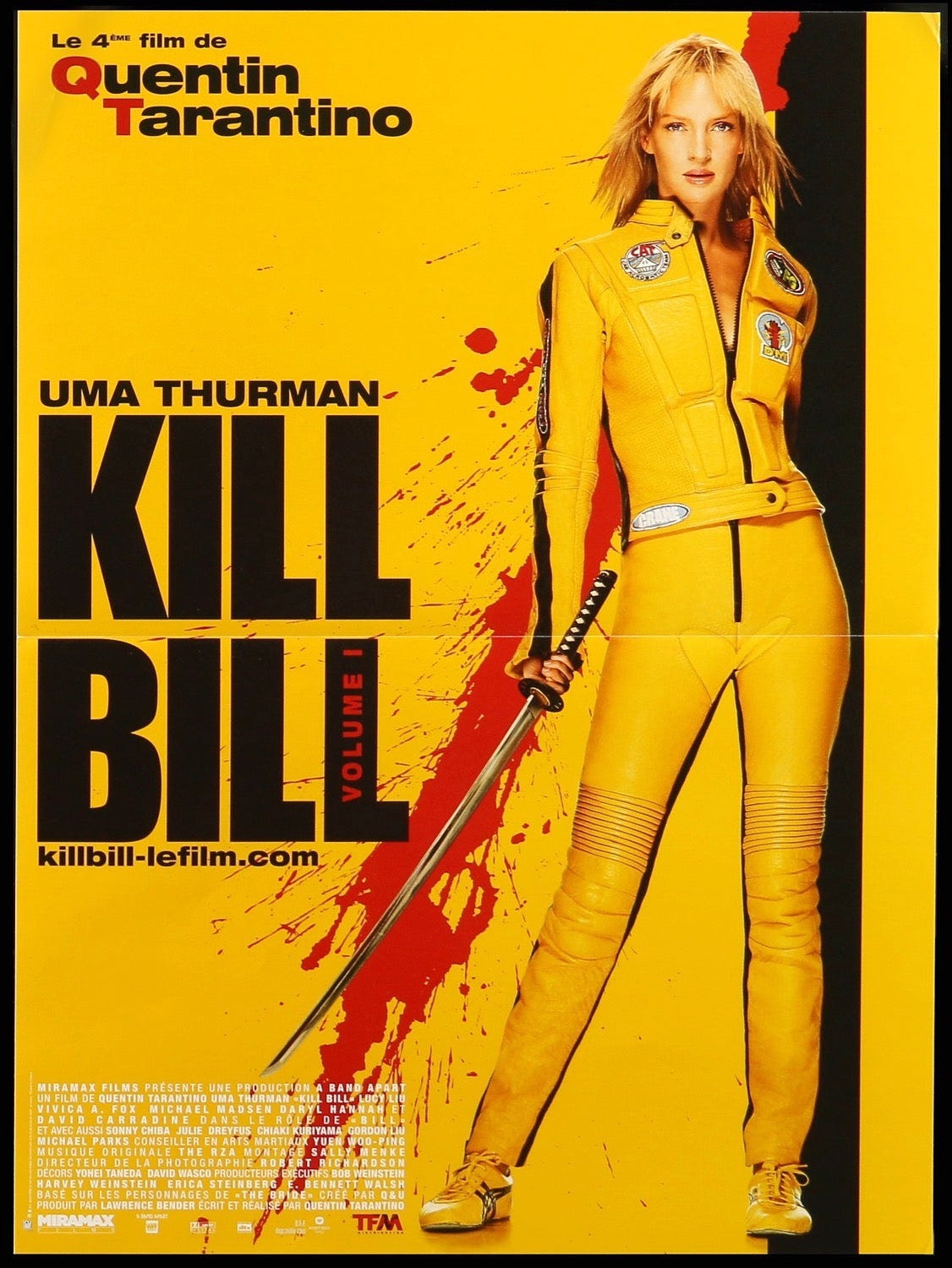

What does Butter’s cover signal to other tube passengers, I wonder – besides the fact that you’re part of an ever growing herd? (It really is everywhere.) Its poisonous insect markings in yellow and red and black, its emphasis on verticality, and the implication of slaughter reminds me of the poster for Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, which I first saw aged three at a Blockbusters. Uma Thurman’s Bride in a deadly bodysuit, rough cut hair, Hattori Hanzo slashing the silver screen, draws from the graphic world of traditional Hong Kong cinema and the legacy of Bruce Lee. On her feet: the yellow Adidas Sambas which have made a stellar return to East London creative wardrobes in recent years.

Thurman was an early glimpse into feminist iconography for me; she seemed to be onto something, even back then, in her Sambas, even when framed with Harvey Weinstein’s Miramax credits and the hideous meanings that they amassed in the time between. I wondered where to place Butter in relation to this.

Butter is a novel about deviant consumption, about women eating when and what and who(!) they shouldn’t. It is about control, consumption, and the underbelly of misogyny in modern Japan. Its reviews take the book at face (cover) value and veer into the ludicrously culinary. ‘Butter will churn your brain and your stomach with panache’ (Pandora Sykes). ‘I will be spoon-feeding Butter to every woman I know’ (Erin Kelly). ‘Butter is a full-fat, Michelin-starred treat’ (The Sunday Times). ‘I devoured this dark and delicious novel’ (Imogen Crimp). ‘It'll make your mouth water’ (Irish Independent). Etcetera etcetera. It’s all very Nigella.

Butter is a book to crave, to consume, to indulge in. But the culture of appetite on which it is marketed inextricably hinges on lack – on not having it yet. In other words, Butter thrives on FOMO.

I’d wager the reader’s real stake is in the purchasing of the book, and in displaying their ownership of it, rather than in the actual reading and enjoyment of it. ‘I was so looking forward to it,’ my friend said to me, ‘but I felt quite let down in the end.’ Perhaps that’s one for the Marxist commodity fetishists to unpack.

Butter was the top accessory at fashion week in March, but it’s almost more useful to think of it as a metaphor for the wider cultural state of play. It stands as the prime example of a marketing manoeuvre that is now standard across industries: the relentless call to consume a popular cultural piece and the promise that our bodies, our intellects, and our emotional worlds (all three!) will be nourished by doing so. See also: Challengers; Babygirl; Eusexua.

If a handful of trendy thirty-something women are saying Butter is a cult-classic worth tasting, must we be seen to sample it too? Carrying Butter around London is to put on a uniform of sorts – the uniform of a certain group who, for want of a better term, are ‘girlies who read on the tube’ (‘girlies’ is gender-neutral). These people are quotidian yet stylish; imaginatively and critically inclined but also with real-life meetings to get to; they are like you, only better.

Beneath the trendiness of Butter’s deportment around the city, I detect a more enduring need expressed in its readership: the impulse to explore how sex/desire can bring us closer to ourselves, and alienate us from ourselves. And how, in a patriarchal world, the (female) body responds to pressures to consume, perform, and be consumed. Reading Butter on the tube is psychogeographic evidence that these questions persist in our daily lives and our commutes. It might be a performance, but as Judith Butler attests in their work on gender, performance ‘constitut[es] the identity it is purported to be.’ To consume art in public is to claim to be something, we just need to ask: what, exactly?

It can be a clutch bag or an Instagram post. Or it can be a book that you can open and stare at while you are listening to the couple breaking up on the tube next to you. At 8am. Rough. What a knob. Maybe I will lend her my copy.

Words by Clare St George