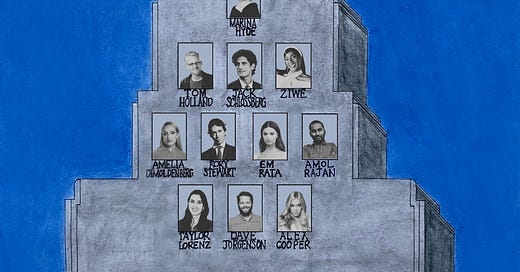

The New Punditry

The modern media landscape can be a discombobulating place. Will Hosie explains how best to make sense of it – and what to watch out for.

Art by Claudia Everest-Phillips

The first person I messaged when I found out Jack Schlossberg was to be made political correspondent for American Vogue was Caroline Calloway. Caroline is someone with whom I am loosely acquainted and whom I very much like. “Caroline,” I began, “I have a question only you can answer. Because you are just about the only person who I imagine has, somehow, come directly across this man.” The question was: what is he like? “Ugh,” Caroline replied. “I fear to report he’s perfect.” And “not to be confused with Connor Kennedy,” she added: Schlossberg’s cousin and Taylor Swift’s ex who attended Harvard at the same time as him.

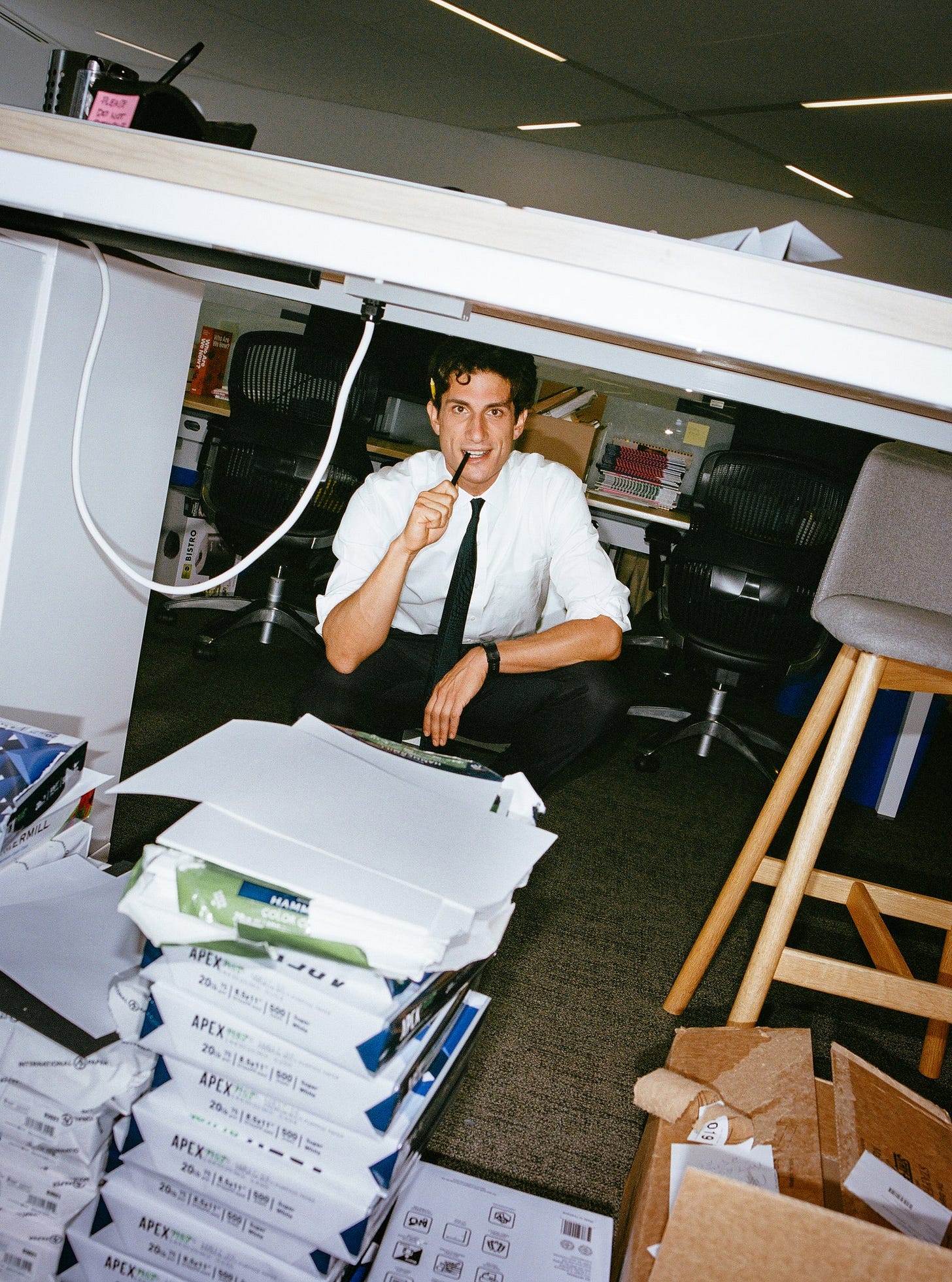

Schlossberg is the only grandson of the 35th President of the United States, John F Kennedy, and his wife, Jackie. Blessed with dynastic genes via his mother Caroline, an attorney, he earned a joint MBA-Law degree from Harvard which he attended from 2017 to 2022. His father is Edwin Schlossberg, a designer, artist and the author of eleven books, who was appointed to the US Commission of Fine Arts under Obama. He counts among his cousins Robert F Kennedy Jr, who is running for office as an independent in the 2024 US Presidential election. Schlossberg was 24 when he attended his first Met Gala. He will now be sharing an office with the people who organised the party.

“Schlossberg is slated to be paid just as poorly as every other Vogue contributor,” the Puck newsletter announced. As a general rule, Gauche is told, that means $250 per article – though rates vary. His contract “requires [Schlossberg] to create up to four monthly Instagram videos of his reactions to ‘key news’ moments in the election cycle” (presumably via TikTok duets) and “as many written articles as he wants to accompany them”. The presidential heir is massive on TikTok (182.4k followers pre Vogue appointment; 355.1k now) and on Instagram (221k pre Vogue; 316k now), where he gained notoriety for goofy videos in which he impersonates stereotypical Americans voters. There’s Jimmy, who supports Biden because he “cares about the economy”; and Anthony, who worries about “Bobby” Kennedy’s pitch to halve the US military budget.

Typical comments on his videos read thus: “Is he on meds, off meds, or just needs meds?”; “I’m 25 and tight btw”. Yes, besides being a Kennedy, Schlossberg is drop dead gorgeous. To search for him on TikTok is to open a Pandora’s Box of compilation videos that see him singing topless, wearing a feathered jacket on a dancefloor and posing in exceptionally tight cycling shorts – usually set to a Lana Del Rey soundtrack (National Anthem, obviously).

The announcement that JFK's grandson was to be made political correspondent – or, as one press release fawned, “combine his background in law and business with the self-described ‘silly goose’ tendencies he displays online” — struck some as absurd; quixotic; nepotistic. Which, of course, it is: but we at Gauche feel this misses the point. The point is it’s engaging. Print publications continue to exist largely thanks to the famous names they are able to score, either for their covers or their mastheads. It generates clicks, traction, and appetite. Because it is only human to love celebrity.

Schlossberg for Vogue is a big get, no matter how pooterish or un-analytical his opinions might be (no one’s buying a fashion magazine for searing political commentary). For him, it’s a reason to wake up in the morning which few dilettantes of his calibre are afforded, and enjoy the clout of working for a magazine that once counted Joan Didion and Noël Coward among its writers. Also, the shoot they did to mark his arrival was very nice and might make for a couple of fab additions to his Raya profile.

Jack Schlossberg in the Vogue offices at One World Trade Center, New York

In 1995, John F Kennedy Jr – who would have been Schlossberg’s uncle had he not died prematurely in a tragic plane crash – launched a political magazine of his own. Named George, it was insider-y and cool and had Cindy Crawford on the inaugural cover. It was never taken seriously by the political class and collapsed after a few years. Schlossberg will have no such trouble: he’s not courting heavyweight readers but those already in thrall to him online. Vogue cannibalises that audience, and he cannibalises theirs: they swell each other’s profiles and everybody wins.

The Schlossberg example is a testament to what the Gauche editorial team likes to call the New Punditry: a school of journalism defined not by erudition but by engageability. That does not mean erudition is discouraged. Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook of The Rest is History are also part of the New Punditry, and exceptionally well read; it’s more that their erudition is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. The end in this metaphor being audience engagement.

A pundit is not quite an expert. Punditry is an expression of expertise: both in the sense that it’s an expert view writ down or broadcast, and that it’s a stylisation of expertise; an inflation of one’s knowledge in a particular field, boosted by the very format (podcast, article) in which the pundit chooses to converse. It’s what happens when fluency and confidence are strong enough to pass off an informed and experienced view as an expert opinion. A Michelin-star chef is an expert; an acid-tongued restaurant critic is a pundit.

In the era of clicks, TikTok and the Death Of Print, confidence begets expertise. More simply put, it’s not what you say so much as how you say it – and as the Schlossberg case study points out, who you are matters too. The New Punditry is rather like a Guy Ritchie film: it usually says nothing new about anything (™ Marina Hyde) but it’s witty, zippy and packed full of action. You leave feeling buzzy, riveted, entertained.

That’s what audiences look for in their pundits too. People are more likely to like, follow and subscribe to content that is gripping over content that is considered: see Jordan Peterson on the right or Hasan Piker on the left (the latter is, like Schlossberg, very hot). This is also true of politicians, of course: Donald Trump and Nigel Farage being the obvious contenders. Even on the sane end of the spectrum, this holds true. People love Angela Rayner precisely because she is ballsy, partisan and regularly puts her foot in it; a soundbite legend. The same goes for Kamala Harris, whose camp turn of phrase is catnip to content creators and who is now leaning more and more into the showmanship we demand from our leaders, forming alliances with actual show-women (Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Charli XCX) to build on an existing audience. Just like Vogue with Schlossberg.

Sometimes, punditry is both gripping and considered. Long-form exposés as found in New York Magazine or The Sunday Times continue to captivate, and do so thanks to, rather than in spite of, their nuance and granularity. The most successful New Pundits™ are those who combine genuine erudition with engrossing detail. The deliciously acerbic Marina Hyde is an obvious contender; so are fellow Goalhanger employees Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell. Across the pond, it’s people like Taylor Lorenz and Ziwe Fumudoh – watch the latter’s interview with drag queen and fraudster extraordinaire George Santos and thank us later.

Others have redefined what it means to be a pundit. Humble enough to know they aren’t experts, these figures have taken a different route. They do not author ideas, but host them. They don’t have to come up with stories; instead, they woo them. Alex Cooper, aka Call Her Daddy, will elicit juicy confessions from Gwyneth Paltrow (namely, that Ben Affleck was more technically excellent in bed than Brad Pitt) as part of a wider discussion on sex and relationships that redefines the celebrity V privacy salsa dance. Amelia Dimoldenberg will schmooze Paul Mescal and Billie Eilish (separately) as well as Hugh Jackman and Ryan Reynolds (together) in a chicken shop, clocking up millions of views. She turns celebrity culture on its head by acting entirely unfazed by the megastars she is interviewing; and in so doing has become the ultimate arbiter of just who is in, or out. Snappy episodes of Hot Ones (host: Sean Evans) or Subway Takes (host: Kareem Rahma) – tighter, more Proustian and more entertaining than a chat show – are entirely set up to produce a soundbite that is destined for a showbiz splash. Some of these give very real pause. As a format it’s modern, peppy, and smart.

Many attempt this same magic and fail: Emily Ratajkowski’s podcast (title: High Low with EmRata and certainly not plagiarised from the massively successful The High Low with Dolly Alderton and Pandora Sykes) ended in 2023. Elon Musk is trying desperately to become a pundit, but anyone who tuned into his interview with Donald Trump last week and heard him burble his way through the joint quagmire of male fragility knows this to be less likely than his hyperbolic ascent to Mars.

The Tesla founder’s logic, though, is simple enough: prove your prowess in one field (say, electric cars) and people will trust you when you speak out of turn (say, on the UK riots or gold medal-winning boxers). Maybe more people would listen to him if he didn’t shitpost so much. In the New Punditry, less really can be more. Cue Dimoldenberg’s monosyllabic delivery and immutable facial expressions – bland, disinterested, and refreshing.

The Chicken Shop Date host recently received an honorary degree from the University of the Arts, London. In her acceptance speech, she spoke candidly about the lack of faith which her teachers had expressed in Chicken Shop Date. It was too niche, they said. People wouldn’t get it. Conversely, a newspaper editor once told me over lunch that his best advice to young journalists would be, precisely, to find a niche. “People never tire of experts,” he said. And of course, he is right. We crave the insider view so much we’ve invented myriad terms for it: the goss, the tea, the scoop, the intel, the 411. But we also value lateral thinkers; opinions that give pause; and those whose apparent expertise spans so far and wide it contradicts the very idea of specialist knowledge. Scholars over academics, as were Darwin, Marx and Freud (thank you, Nassim Nicholas Taleb). An expert, by definition, cannot be ubiquitous. This is where the New Punditry steps in. It is also where the problems start.

Amelia Dimoldenberg and Charli XCX on Chicken Shop Date

In a 1997 interview with Jay Leno, Fiona Apple declared that she was not shy, as most people accused her of being, but rather tactful. “I just don’t speak if I don’t have anything to say.” The modern media landscape is a rich and exciting place: but it is also tactless. To be sure, the tradition of columnists punching above their weight on topics they know little about is practically historic. But the checks and balances required to verify facts and assert trust are dissolving. New media eludes the rules that were designed to regulate the press. Pundits are freer than ever to spread disinformation in the name of free speech – the real-world consequences of which can be catastrophic, as seen with the racist riots across England this summer.

Much of the pressure commentators feel to cross over into territory that is not in their remit stems from the plasticity of the internet. It’s the premise of the Wikipedia game some might have played at dinner parties: where you need to get from one article to another by clicking on as few hyperlinks as possible. How quickly can you get from the Wikipedia entry for Rihanna, say, to that for the Vietnam War? (The quickest we’ve ever done it in is four, but we’re happy to be shown a faster route.)

The internet has given us access to a library of information hitherto unprecedented: you can leapfrog from one topic to the next and do just enough research to pass off your opinion as gospel. Also with that volume comes malleability. Facts can be reshaped and recontextualised; lines redrawn; conclusions shattered. This decentralisation – or democratisation, apologists would say – is the root of modern media: of microtrends, echo chambers and conspiracy theories. In the right hands, such a wealth and diversity of information can assist with analysis, lead to important breakthroughs and serve as a zeitgeist monitor. In the wrong hands, like those of Elon Musk, it can create silos, threaten our ability to think and encourage violence.

Telling the right hands from the wrong uns – the experts from the frauds – is not always an easy task. They both exist under the umbrella of the New Punditry, with a fluency and loquaciousness that are often equal. It takes just one convincing fraud to flirt with conspiracy theory to legitimise it. Speaking quickly, as Jordan Peterson does, works incredibly well in such a landscape: people crave speed due to shorter attention spans and respect it because it sounds like the pundit knows what they’re talking about. (Note for Elon: ‘quicker’ does not mean ‘more’ or ‘incorrectly’.)

Speed engages us, and always has. We value a wit for being pithy, but also for being quick. But it can also be corrosive, and speaks to a culture that forgoes consideration for fast-paced, headline-grabbing moments. It happens across the board: the Rwanda policy, Baillie Gifford V Fossil Free Books, etc. People rush to conclusions that make little sense and have disastrous consequences. Audiences then act outraged: but they are complicit in the very culture that brings this all about. This writer included.

We are seduced by the clickbait; the hot-off-the-press; and the hot full stop (hi again, Schlossberg). We know it’s bad for us – like sugar – and yet we continue to participate willfully in an economy of speed and scale that we know is dangerous. Twitter, now X, exploits our anger because it keeps us on the platform for longer (a fact masterfully exposed by Jaron Lanier in his book, Ten Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now). Brands flogging new products do it too: they know criticism is more of a hook than praise, and script their adverts as if it were a diss. A video titled “Ten things I hate about the BMW X1 luxury compact SUV” will then reel off ten compliments about it.

Even if we do cut down on our consumption of media promulgated on and by Twitter/X, what are we actually achieving? When public figures – journalists, MPs and yes, pundits! – announced last week that they were boycotting the platform because it’s become too much of a cesspit (or, in the words of one Times columnist, because its owner is a dangerous troll), aren’t they just making the problem worse? By their absence, will they not simply allow right-wing extremism to grow uncurbed on the platform even more?

Elon Musk, who owns X, endorsed Donald Trump in the US election during a rambling interview on the platform.

In 1973 Tom Wolfe and E. W. Johnson published the first anthology of The New Journalism, a compilation of the sort of non-fiction writing that flourished in America in the 1960s, across topics from baton twirling competitions to the Vietnam War. The stars of the new school were Truman Capote, Joan Didion and Robert Christgau; their vessels were Esquire, Rolling Stone and New York Magazine. Some of those publications continue today as agenda-setting, news breaking platforms (it was New York Magazine, not the New York Times, that broke E Jean Carroll’s first-hand account of being attacked by Donald Trump in Bloomingdale’s). Others, the Guardian trumpeted in June, are “now as defunct as the clay tablets of Babylon.”

Media is changing at a speed commensurate with the rapidity of new pundit speech: that is to say, very fast. Pitchfork has been swallowed up into GQ. The Evening Standard is going weekly. Relative newcomers like Vice and Buzzfeed have been either shattered or swallowed up (though Vice itself is a curious one, with the founder and former CEO Shane Smith coming back as editor-in-chief after he ran it into the ground; failing upwards and all that). The old guard is leaving: Paul Webster from The Observer; Pete Clifton from PA; Pete Wells from the New York Times. It sounds a lot like the 2023 Booker Prize shortlist, higher in apostolic names than in women – or, if your thinking is that way inclined, like the era of the white, middle-aged male hegemony is finally coming to an end.

What was interesting about New Journalism was how it changed non-fiction writing. It became more storylike; digressive; unbound. Features became novellas. As the years went by and word processing software on computers became more and more developed, more freedom was given to writers to revise and re-edit their work – the result being more authorial articles with a polished feel. Style has evolved according to tangible, material changes to the technology that supports the writing. Fast forward to today, and a new vernacular inspired by the internet is changing the very way we craft a sentence. The New Punditry, for its part, is shaped by editorial demands for online virality and, in the case of podcasters, soundbite-heavy broadcast snippets that are necessary for promoting a show.

How virality is achieved depends largely on a publication’s audience. Vogue knows its readership will respond well to a beautiful nepo baby like Schlossberg – whose column is called Jack Reacts, which says a lot about the way journalism is evolving, like a private conversation prompting thoughts and answers (“reacts”) communicated at ever greater speed (who needs sentences when you have emojis?). The Telegraph, meanwhile, knows their readership will respond well to controversial right-wing commentators. The Guardian doesn’t know their readership quite as well as they think (many loyal subscribers believe it’s gone too woke and forgotten its core values, Gauche has learnt). It is – allegedly – in trouble as a result.

In the era of the chronically online, where everything we do is to some extent a performance, the line that once existed between an anchor and a pundit has changed. Figures like Amol Rajan and Dave Jorgenson tow the line, but ultimately shape public opinion even if the former is bound by the BBC’s impartiality clause. The topics which he chooses to discuss on the Today podcast – and the facts he chooses to share – become the narrative.

More and more, pundits are expected to respond to Google Trends and are at the mercy of search engine politics. There is something to be said for this, of course: pundits should respond to the zeitgeist lest they wind up irrelevant. But when everything moves so quickly, and the zeitgeist is so fickle, we need to think about what gets lost in such an endless forward motion – in this unyielding acceleration of words and ideas. And, more crucially, about what is gained by those who exploit this phenomenon to unsavoury ends.

The original cover of The New Journalism, ed. Tom Wolfe (Harper and Row, 1973)

an excellent sharp and saucy read