It’s the talk of the town – or at least the chattering classes. Slave Play, the work of Yale alum Jeremy O’Harris (Gossip Girl, Emily in Paris), with 12 Tony nominations under its belt, has come to the West End.

Press night saw five walkouts. “The last act is difficult to watch,” says playwright Zoe Bourdin. “I haven’t fully sorted through how I feel about it.” Actor Jack Donoghue echoes this view. “I’m going to need a significant amount of time to process my thoughts,” he tells me. “There’s a lot to unpack,” culture critic Nancy Durrant wrote on her Substack. “Some moments … are truly shocking.” In a four-star review, The Standard’s theatre critic Nick Curtis called it “an elegant, essential provocation from a singular writer whose voice – needling, sly, hyper-aware – demands attention.” Consider that demand met.

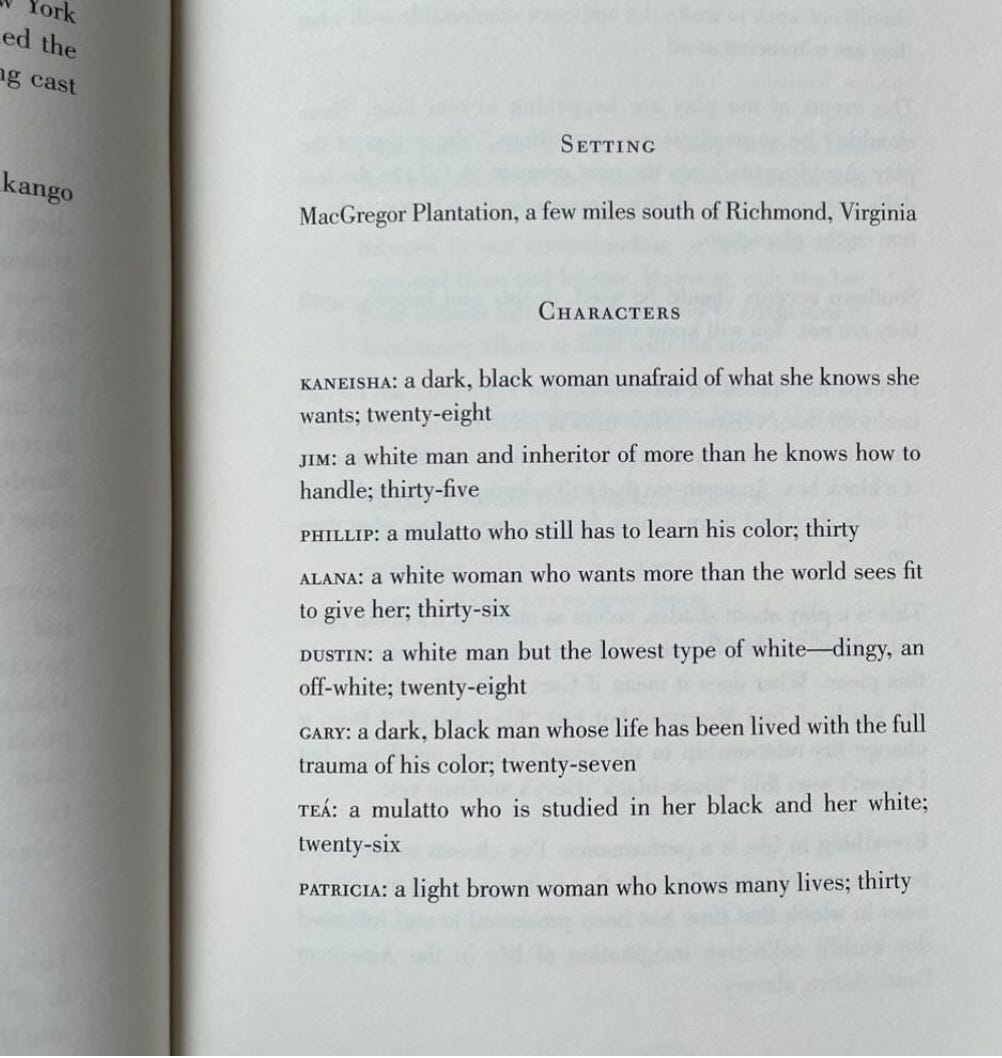

O’Harris’ drama is a refreshingly hostile, fraught and complex piece of theatre. Three mixed race couples, in which the black partner has lost their mojo, attend a radical therapy course in which slave play (i.e. sexual domination with a pre-Abolition theme) is used to rekindle their flame. The couples dissect their respective performances as they grapple with big, potentially insurmountable questions about sex, race and the power dynamics in both. It is challenging, at times enervating and often very funny. Slave kink, race fetish, therapy jargon and ideological purity are all varyingly mocked and validated.

Some described the absence of a clear message as vexing. This is to miss the point of a play that revels in its own messiness. My friend Emma Loffhagen, a mixed race black woman in an interracial relationship, says: “It’s interesting because it’s so taboo. I don’t know how you could approach that subject matter without being very messy.”

First performed in 2018, Slave Play offers a prescient exploration of the breakdown of identity politics. The idea of race perception is dealt with especially interestingly. A Latinx character (labelled both “off-white” and “eggshell”) and one who is mixed race deliver powerful speeches that lead us to wonder whether, despite our multiethnic society, we can ever escape the white gaze. It also considers the possible impact of the black gaze, a controversial idea which, depending on your perspective, is either racist (suggesting a level of power that has been historically denied to black communities) or the opposite (denying this power would be to condemn the black community to perpetual victim status).

A curse of much new writing today is that authors or dramaturges feel pressured to produce ‘politically engaged’ art, which often ends up sending a message so stuffy, so painstakingly clear, it breaks the cardinal rule of show-don’t-tell. Though parts of O’Harris’ script are predictable and ripe with political clichés, it never falls into that trap. Instead, it chooses chaos, and succeeds.

Many will see a play about slavery and, therefore, a play about America. For such an audience, O’Harris’ drama risks falling on deaf ears. But more than a play about racism in the United States, this is a play about how we perceive race, delivered by actors who – per casting intentions – embody literalised identities – say, “a 30-year-old light-skinned black woman” – which are relentlessly tested, probed and delimited over two hours, sans interval. We put ourselves in boxes: but, O’Harris asks, at what cost?

This lends arguably more poignancy to the two blackout nights which the playwright has arranged for Slave Play’s West End run – the first of which was last week. When these were announced in February, Downing Street exploded. Then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called the move divisive, much to O’Harris’ amusement.

O’Harris is not one to shy away from controversy. In a recent episode of SubwayTakes, he said that “white people, in their nature, have a colonising spirit”. Does he really think this is true? O’Harris comes across similar to Azealia Banks: say something facetious and people will listen. A friend who recently interviewed him for a UK magazine informs me he’s “fully bought into” his new role as “a party girl”. Flippant comments should come as no surprise.

Blackout nights, though, feel sincere and necessary. Writing in the Evening Standard, Loffhagen convincingly argued that watching a play as a black person, surrounded by a majority white audience, can feel singularising. There is comfort and empathy to be found in an audience in which you recognise yourself.

Slave Play deals at length with the commodification of black bodies. Those who’ll have the hardest time stomaching it, Durrant suggests in her review, are black women. “There’s a lot on the production’s website about self-care,” the former Arts editor of the Evening Standard writes in her Substack. “I don’t think it’s the white audience members who are going to need it… put it that way.”

More puritan critics will struggle, as they would with any story in which no one comes away unscathed. For so long, culture has demanded we have goodies and baddies – or at least, to have someone or something to root for no matter how flawed. O’Harris, 35, has created a drama that transcends these categories and is unapologetically innovative in its consideration of both timeless and hypermodern issues. “I think the play goes beyond good or bad,” agrees Zoe Bourdin. It is the most important piece of theatre on the West End today.

Slave Play is on at the Noel Coward Theatre until 21 September