The Oxford English Dictionary word of 2022 was goblin mode. Which, if we’re being pedantic/numerate, is in fact two words and therefore should not qualify. It is also an activity/mode of being that should not be encouraged. Anyhow, another word that was having a real moment in 2022 was zhuzh. Those who know, know. Those who don’t should read on.

Is it ‘zhuzh’, or ‘zhoosh’, or, as Carson Kressley favours, ‘tszuj’?

The dictionary definition of ‘zhuzh’ is straightforward: ‘To make something more interesting or attractive by changing it slightly or adding something to it’. Its etymology is more complex, weaving multiple strands from the Royal Navy to the travelling circus, to Yiddish, to pure onomatopoeic appeal. The linguist Paul Baker claims that the word is Polari: ‘A secret form of language, used mostly by gay men in the early 20th Century’.

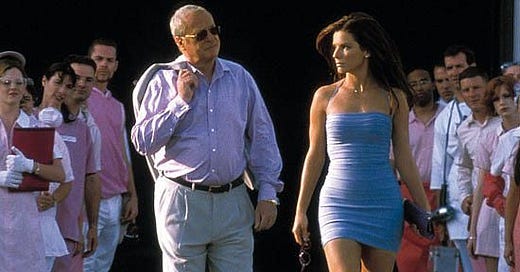

Baker’s is a convincing argument given the enduring association of ‘zhuzh’ with queer communities today. It is a term, after all, that was introduced into mainstream culture by Kressley in his 2003 show, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. When asked where it came from, Kressley claimed to have encountered ‘zhuzh’ when working at Ralph Lauren, a company incidentally owned by the son of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants – a context that captures much of its etymological texture.

Whatever its actual origin, ‘zhuzh’ has appeared and reappeared in displaceable and often marginalised communities over the past century. These were people who moved, who travelled, and who adopted multiple ways of being and seeing. These strategies resulted in alternative ways of measuring aesthetics. It is adding glitter not removing it; it is popping a collar, not flattening it. The term, in both meaning and practice, seems also to simulate the contingency and often ‘secret’ rules of its etymological roots.

JVN, the hairstylist of the 2018 reboot of Queer Eye, would frequently delight in ‘zhuzhing’ the hair of the episode’s ‘straight guy’. It is likely that this man, this “Steve”, had not left his house in years, or was locked in a stalemate with his family, or owned a wardrobe that resembled an eighties catalogue. Crucially, in those moments when JVN was summoned, like a silky-haired Svengali reciting sermons in uptalk and smelling of neroli, they were never aiming for a specific hairstyle or styling technique with ‘zhuzh’.

Rather, they were making a promise. A promise to, somehow, make Steve’s hair better. To make the hair utterly present and relevant to the fact of Steve. And to somehow, through the ‘zhuzhing’ of the hair, make Steve a better person.

‘Zhuzh’, then, in both origin and execution, is a practised improvisation with covertly high stakes. Plump the cushions; then, this will be the house of your dreams. ‘Zhuzh’ is about alteration and addition rather than obliteration. Something as small and simple as a well-placed gesture (blink and you miss it!), is needed for ‘zhuzh’ to be performed. Its action is miniscule; its effects, however, claim to be giant.

If an architect announced a plan to ‘zhuzh’ the main road – or a politician a country – we would be both entertained and deeply unsettled. ‘Zhuzh’, speaks to a more temporally and spatially collapsed form of alteration. It is manual, improvisatory, and preferential. It promises to change something only within the present moment – for the sake of that moment. ‘Zhuzh’ cares not for the history or longevity of itself as a performance. It is entirely contingent and a means to a different end. While the result of ‘improving’ is an improvement, or that of ‘restoring’ is a restoration, we do not have a vocabulary of zhuzhment or a zhuznaissance. The effect of ‘zhuzhing’ is never about memorialising the ‘zhuzh’. Zhuzh is a performance that must dissipate. This is the key to its stylish ease.

Perhaps this is why efforts to market such a concept seem deeply ironic. When asked how long a bottle of Zhuzh! lasted, a self-tanning company of the same name responded on their FAQ page: “two years”. A two-year zhuzh is not a zhuzh; it is a certified slump.

‘Zhuzh’ is a practice of sublimating the extraordinary through the ordinary, the desirable through the disgusting, the luxury through the budget in the smallest possible move. Zhuzh speaks: I have made this object, this hair, this meal, this tweet better than it once was, through a purposeful, minute, and instant action.

Being asked to zhuzh something up is both the clearest and least helpful directive: it demands that you improve a draft with a sleight of hand or turn of phrase that is discrete yet unrestrained. It eludes explanation, an epistemological anomaly that puzzles all but its agent, solely responsible for the transformative act where zhuzh is the instrument of choice. It’s both a means to an end and, by virtue of zhuzh’s scarcity, an end in itself.

Zhuzh sees the gauche and the gaudy for what they are: not as points of departure, but as destinations; the bland and banal ripe pickings for our cultural curators to zhuzh them into shape. Zhuzh, relishing its own nebulous queerness, celebrates the very quirks which imbue it with significance.