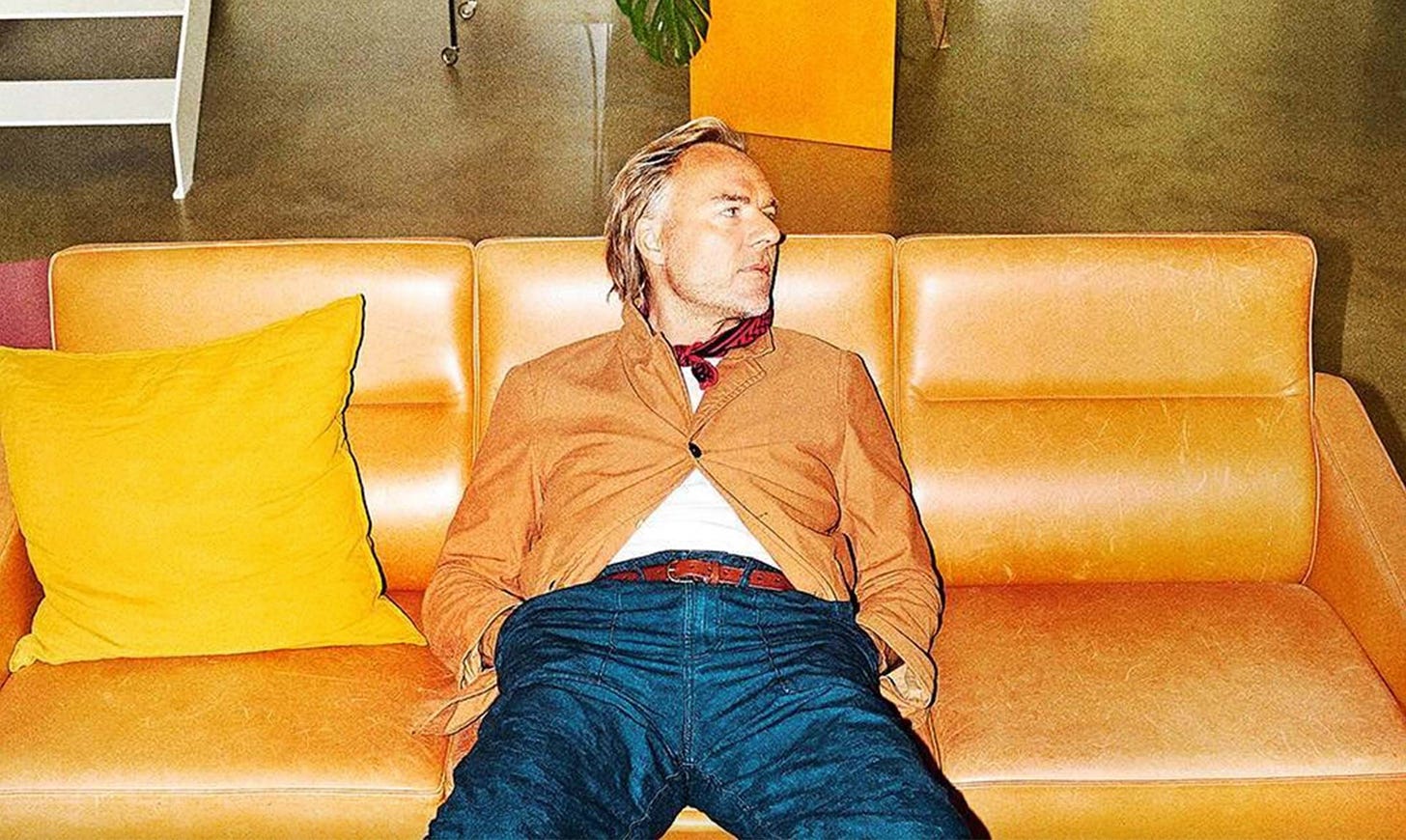

Meet Jan Gleie: the man behind the vignette

Will Hosie speaks with a legend of fashion film and photography about his new exhibition, Dioramalism

The first thing to know about Jan Gleie is that he is colour blind. To the layman, a colour blind artist might sound much like a chef with poor tastebuds, or a composer who is hard of hearing. One look at Gleie’s paintings, films and photographs swiftly dispels this false equivalence. As the winner of the 2012 Cannes Lion for Creative Effectiveness, the director of the award-winning H24 Hermès campaign and the man behind Instagram’s current obsession with the vignette (see @nicoleo and @louisaws), Gleie’s distinctly modern eye is the subject of a new exhibition opening next week in Copenhagen. Its title: Dioramalism.

The idea of an exhibition came about a year and a half ago. “I tend to work backwards,” Gleie says. “I believe that when you can visualise something – truly visualise it – you can make it happen.” At age 58, Gleie is visualising a future that is “more internal, more artistic”. An exhibition comes as no surprise. “I’m entirely self-taught,” he says. “I did my first oil painting at ten but stopped in my twenties and only took it up again recently.” Film and photography have been his primary mediums in the intervening decades.

Gleie has become something of a legend in the world of fashion – with campaigns for Hermès, Vivienne Westwood, LVMH and Adidas under his belt. His work has received plaudits and ovations at Advertising Week New York and Cannes Lions ceremonies. But it is the world itself that fascinates him: the freeze frames and idiosyncrasies invisible to the naked eye but that of the artist.

Gleie was born in 1966 in Copenhagen. “I was born into a commune, except it was my family,” he says. “I lived in a house where my own family was on the ground floor; my grandparents on the second floor; my gay uncle and his boyfriend lived in the attic [ed: closer to God!].” It sounds like Charlie and the Chocolate factory, only more affluent. “It was a house with a lot of internal traffic,” Gleie laughs. “I spent a lot of my time upstairs with my grandma. Both my great-grandparents had been artists; that floor of the house was like a cave of imagery; dark walls with dark frame paintings with faces and landscapes.”

He went on weekly outings with his grandmother to the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen. “It was my favourite place,” he says. It was there that he discovered the diorama: an art form in which a scene is replicated as a three-dimensional model either in full-size or in miniature. Gleie is more eloquent and visual in his description: “Dioramas are like little worlds,” he says. “Like when you put a stuffed antelope on a fake desert background and you paint the horizon and put fake trees in three dimensions…

“I like enclosed spaces,” he goes on. Dioramas were impressive because they felt “like a heightened reality”; “artificial, but very real landscapes”. “I realised a couple of years ago that all my images are little dioramas,” he says. Dioramalism is a portmanteau of diorama and realism, subtitled Still And Moving Images.

“I’m very traditional and conservative, in many ways,” Gleie says. “I like the film format, and the oil painting format. I’ve always wanted to do what the great painters could do.” And yet his impact has been something very modern. By all accounts, the Instagram trend of 2024 has been that of the vignette carousel: short films, 10-12 seconds each, each a single frame; the camera unmoving. The lyrics to Everything is romantic – bad tattoos on leather tanned skin, neon orange drinks on the beach, lemons in the trees and on the ground – not only provide an accurate transliteration but show just how far our culture is obsessed with the metonym. Gleie was the first to pioneer this sort of filming: the romance of a single drape dancing to the rhythm of the wind; a warm, flashing light above a bathroom mirror, illuminating things intermittently; and the imaginative effort required from the viewer to picture the frame beyond the frame.

Dioramalism owes as much to Gleie as to his wife, Barbara Hvidt, a designer and fellow photographer. Being colour blind, Gleie will work with her when painting; he will sketch the outline and she will number the various parts of the painting according to a nomenclature that assigns a colour to a digit. The result is some of the most meticulous and expressive colour work in the business. The show is sure to be a triumph.

Meet the artist: Jan Gleie

Favourite colour: Muted and earthy tones

Favourite book: Narcissus & Goldmund by Herman Hesse

Favourite film: The New Land by Jan Troell

Favourite artist: Marina Abramovic

Favourite musician: Sid Vicious

Dioramalism opens on 28 August at Montegarde 3, 1116 Copenhagen