Charmed, I'm sure

The perfect accessory for a world in financial meltdown is a £195 keychain in the shape of Lorazepam

Do you hear that? A faint jingle in the distance, the distinctive clattering of a Coach cherry bag charm, the squeak of a well-heeled tamagotchi, the swish of an Hermès handkerchief in the breeze… Or is it just the rattle of a holiday keychain?

For half a year now, the bag charm has been a favourite accessory of the fashion elite. Supposedly the renaissance of a naughties trend (isn’t everything these days?), it first resurfaced during the SS24 shows (October 2023), when Balenciaga and Miu Miu adorned their bags with keys, chains and cords galore. A year in, the trend had caught on – and it has endured and disseminated ever since. Even sleek Scandi girls were blinging out their bags with miniature paraphernalia at Copenhagen Fashion Week in January. It’s official: microtrends are over.

There are many theories behind the re-ascent of the bag charm. One of the most wholesome bills it as an homage to the late Jane Birkin, who decorated her namesake bag with trinkets and talismans. Nothing says self-expression, commentators would have you believe, quite like a beaded necklace tied around to the handle of a tattered, vintage Hermès.

Emily Austen, CEO of the marketing agency EMERGE and author of Smarter, recently created dinky book charms to promote her recent bestseller. “As the world is seemingly self-imploding,” she says, “we look to the only time and space that represents safety and harmony, the idealistic, nostalgic past.” Cheery – and in light of last Wednesday’s tariffs hike, uncomfortably true.

Courtesy of Emily Austen

Fashion has been hit hard by Donald Trump’s announcement. Lululemon shares dropped over ten percent, while shares of Nike and Ralph Lauren fell seven percent. “Over 97 percent of apparel and shoes in the US are manufactured overseas in countries like Vietnam,” The Cut reports, “which is a major supplier to brands like Nike and is now dealing with a 46 percent tariff.”

Along with carmakers, tech companies and whisky manufacturers, clothing brands are among the UK sectors thought to be worst-hit by the policy. The US is a major sales market for UK retailers such as Doc Martens, Watches of Switzerland, Asos and WH Smith (soon to be renamed TGJones). Watches of Switzerland shares plunged by 15 percent in one afternoon, while shares in fellow British giant JD Sports fell by nearly five percent.

GaucheGirl™ Lily Allen and her Hermès bag charms

At first sight, the link between bag charms and global financial panic might seem a bit tenuous. Trinkets trade on the currency of ‘cute’, and are themselves an adaptation of the Japanese love for かわいい (kawaii). It speaks volumes that along with ‘konnichiwa’ and ‘arigato’, it’s one of the only words that non-Japanese speakers are likely to know – and arguably the country’s biggest cultural export, with examples ranging from Hello Kitty to Gwen Stefani’s Harajuku girls.

Cute, however, hides a multitude of sins. In her book Our Aesthetic Categories: Cute, Zany, Interesting, the American literary critic Sianne Ngai describes the first of this triumvirate as ‘an aesthetic response to the diminutive, the weak, the subordinate.’ In other words, cute is cute because it’s small and in need of our protection. Cute things are also harder to be mean about – a neat way for a stylist or designer to eschew at least the public ire of criticism.

And while it’s easy to privately skewer the kawaii trend as tacky, a more valid critique might point out the hypocrisy of a style that now bills itself as the antidote to stealth wealth, while simultaneously commodifying the kind of trinket that looks like it could be bought for nothing in a souvenir shop. In the same way the dominant trend of the last two years – quiet luxury – has been about putting an absurd price on basic clothing (a white tee, say), the trend for bag charms is about putting an absurd price on what’s effectively a glorified key chain. You need only look at Hermès’s £670 leather pegasus charm (available in multiple colours), or Prada’s teeny, tiny, £540 teddy bear charm to know “rich” and “kitsch” are once again two sides of the same coin.

So many of these miniatures are of food – and go hand in hand with the miniaturisation of meals (small plates) and appetites (Ozempic)

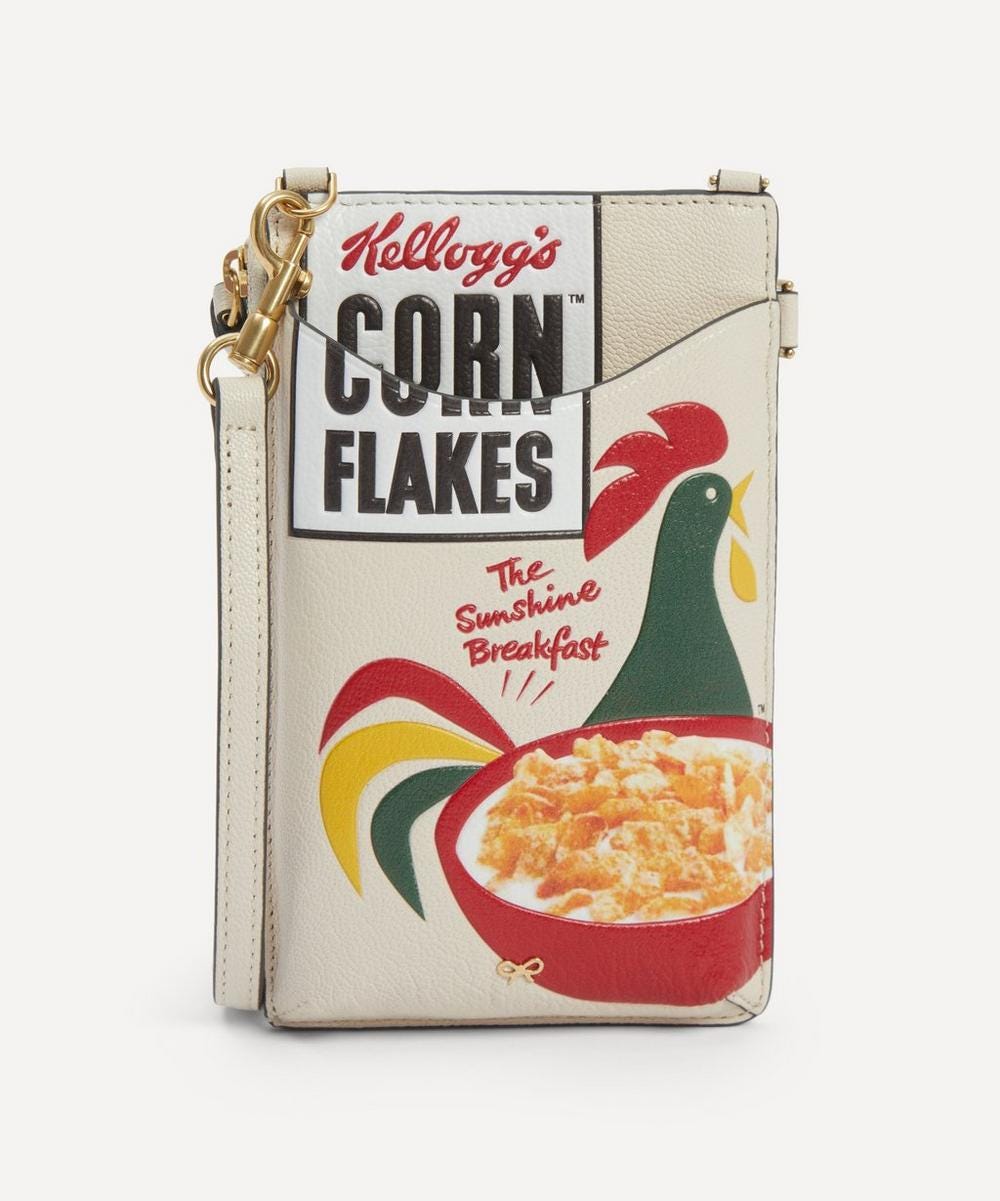

Few have capitalised on the vogue for the small and flashy quite like British designer Anya Hindmarch, who in recent years has turned away from traditional leather totes and made a business of reproducing inexpensive objects in leather miniature – whether that be a sachet of ketchup, a pack of polos or, most recently, a Mr Muscle™ branded sponge, all retailing for upwards of £175.

Anya Hindmarch’s Cornflakes Zip Pouch, £450 (Liberty, London)

The popularity of these replicas is indicative of something larger than bag charms (or, for that matter, fashion). In a world where wealth inequality has never been so high, flaunting a £425 Loewe Olive keyring on an even more expensive handbag when many can’t afford to eat feels a bit like flirting with the guillotine. Chic, maybe. But cute? Not so much.

Are we surprised, though, that we’re now at a stage where even the trivialisation of wealth has been commodified? Bag charms, for all their display of the mundane and the minute, are like a rich person’s parody of regular life. The world of the bag charm is a world where French Fries (Fendi) cost £600 and Nurofen costs £195 (Hindmarch), coveted by the sort of people who (obligatory Succession reference) probably couldn’t tell you the price of a gallon of milk.

It’s interesting, too, that so many of these miniatures are of food – and go hand in hand with the miniaturisation of meals (small plates) and appetites (Ozempic).

Yet the gilded cage that holds the purveyors of luxury bag charms is not so far removed from most people’s every day. In the real world, too, basic items are becoming unaffordable. Biden-era inflation and a more recent avian flu outbreak have hiked the price of eggs in the US; they now cost 80 percent more than they did at the start of 2024. Luxury is no longer something for people to buy into – it’s thrust upon the masses as inevitable.

The bag charms of SS24 were, far more than an early reaction against quiet luxury (or, as Vogue hilariously termed them, an “entry point into luxury” – our emphasis), the harbingers of a new world order in which rarefied price points seep into our daily lives. For some, it’s all fun and games. For others, it’s pauperising.

Hindmarch may be flogging a £195 leather clutch in the shape of a pack of Nurofen, but with financial anxiety levels at an all-time high, surely the perfect accessory for the current market meltdown is one shaped like a bottle of Lorazepam.

This was SO GOOD. Feels like it's been months since I've read journalism which simultaneously (and so deftly!) wittily entertains and actually informs. There was nothing hedged here; no coyness---it was spirited, real, and challenging. The kind of writing which is a privilege to read and engage with: you know it's the product of real thought coupled with creative executive handling. Such a shame that such a wholesome trend which actually allows for personality in fashion and (okay this is trite) 'heals the inner child' - keychains, handmade friendship bracelets, ribbons - has been gentrified.